Last Updated on August 2, 2021

We all have certain movies we love. Movies we respect without question because of either tradition, childhood love, or because they’ve always been classics. However, as time keeps ticking, do those classics still hold up? Do they remain must see? So…the point of this column is to determine how a film holds up for a modern horror audience, to see if it stands the Test of Time.

DIRECTED BY ARTHUR LUBIN

STARRING CLAUDE RAINS, NELSON EDDY, SUSANA FOSTER, EDGAR BARRIER, HUME CRONYN

One horror story that has proven itself time and time again, and for damn near a century now, is Gaston Leroux’s unshakably durable THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA. The first big-screen iteration of the classic horror tale came about in 1925, and has been adapted no less than a half dozen times since, most recently in 2004 with Joel Schumacher’s largely adept adaptation. Hell, De Palma made a version in the 70s, Robert Englund one in the 80s, and Argento one in the 90s, which speaks directly to the staying power of Leroux’s story. But what about the 1943 version? What about the way in which this story was adapted in a time when Universal was not only the best game in town in terms of monster movies and outright horror yarns, but dedicating their best and most decorated resources to the horror genre? And what about the glorious Technicolor applied to the story for the first time?

Thankfully, Universal has recently issued a gorgeous new Classic Monsters Complete 30-Film Collection on Blu-ray, which gives us a great opportunity to answer these precise questions. As Arthur Lubin’s THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, we shall see how this version of the age-old horror tale has either defied father time, or suffered serious senescence!

THE STORY: Loosely adapted from Leroux’s novel by screenwriters Eric Taylor and Samuel Hoffenstein, this iteration of THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA wisely retains the setting of the famed Paris Opera House. Renowned violinist Erique Claudin (Claude Rains) is confronted by the opera conductor Anatole Garron (Nelson Eddy) about his discordant performance. Claudin ensures that he is fine, but we soon learn he has begun losing feeling in his left hand and his music is suffering as a result. Desperate to keep this a secret, Claudin is also financially bankrupt after spending all of his money on voice lessons for Christine Dubois (Susana Foster), an elegant ingénue with an angelic soprano. In attempt to make some fast cash, Claudin takes a piece of music he’s written to a music publishing house. Jilted at first, Claudin turns into a homicidal maniac when he hears his own piece of music being played by another musician in the other room. Claudin lashes out, is splashed in the face by caustic green etching acid by a servant, before ultimately strangling a man to death.

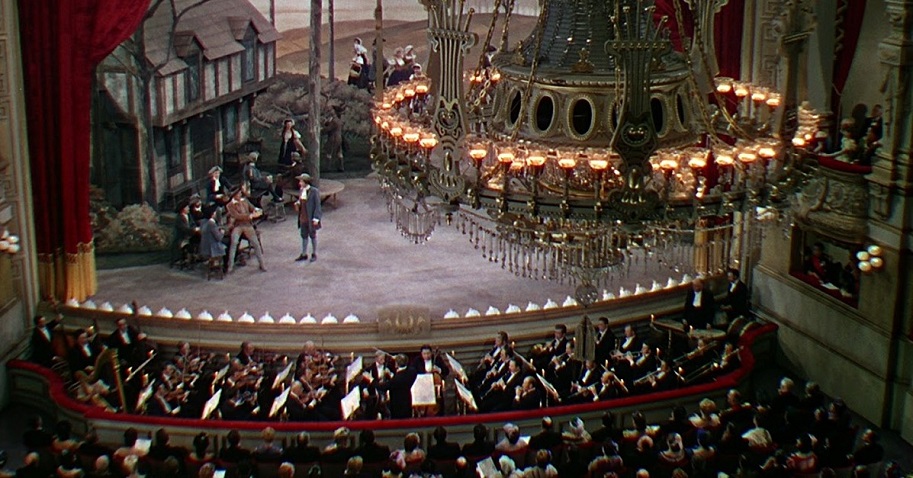

Now on the run, Claudin retreats into the moldering caverns of the sewage-way beneath the sprawling opera house, where he skulks in the shadows, donning a mask, cape and brimmed-hat. Claudin begins terrorizing the performers aboveground, hell-bent on ensuring that Christine is substituted for the leading role. All the while, a hilarious subplot involving identical looking suitors – Anatole and Inspector Raoul Dubert (Edgar Barrier) – vie for the affections of Christine, who frankly wants nothing to do with either. Lubin has fun with this strand of the narrative, even going so far as to have the identical-looking suitors speak the same lines in unison at one point, reinforcing how similar they are. Anyway, on opening day, Claudin deceptively sneaks his way onto the stage, in full disguise, and blends in with the vast array of similarly masked and costumed performers. Everything comes to a head when Claudin climbs up into the rafters and slowly saws the chain of the gigantic chandelier until the entire ornate structure goes slamming down on the stage. From there, the frenzied finale!

WHAT HOLDS-UP: We already addressed how durable Leroux’s story itself has proven to be over the course of 93 years and one-half dozen cinematic adaptations. But having just reviewed Lubin’s 1943 version, there seem to be three foundational bedrocks that have kept the film proudly propped upright for the last 75 years. Said newels and balusters include the Academy Award winning cinematography and production design, the outstanding performance by horror veteran Claude Rains, and the films ferocious finale!

Shot by Hal Mohr and W. Howard Greene, with the production designed by Ira Webb, John B. Goodman, Russell A. Gausman and Alexander Golitzen – the sheer size, scale, scope, sheen and absolutely beauteous Technicolor enhancement of THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA is beyond reproach. Seriously, it remains one of the most handsome and elegant productions one can recall, a feat made all the more impressive considering the movie was in the middle of WWII. Adjusted for inflation, its $1.75 million budget would equate to roughly $26 million in today’s dollars, which gives you an idea of how much Universal thought to invest in such a well-known story. To wit, the same Universal back-lot that the 1925 silent version was filmed on – Stage 28, the oldest standing film set in the world, which is purportedly haunted – was used again here to replicate the sprawling Paris Opera House. A brilliant decision, as the production value couldn’t be more ornately suited for the material.

By filming in such a gargantuan area, Mohr and Greene deftly use the space to great effect with their graceful, balletic camera sweeps, deft uses of focal depth – simultaneous foreground and background action – the dripping candlelight, flickering fireplaces, sinister shadows, etc. And they do so in a way that feels germane to the drama pertaining to the stage. The camera movements aren’t at all superfluous or visually distracting, no, they adroitly mirror the action taking place. It’s what they teach every damn film student on day one, no unmotivated camera moves. Mohr and Greene present a master-course in this theory, as every frame of the film, every placement of the camera, every close-up juxtaposed by a long-shot, is expertly crafted. I urge you all to indulge in splendor of the Blu-ray restoration of the film, as it crystallizes how deserving of the awards the cinematography and art direction were at the time, and how much they still retain their sumptuous luster in 2018.

Another aspect of PHANTOM OF THE OPERA that worked so well in 1943 that cannot be dismissed with fresh eyes now is the turn of Claude Rains as the titular terror. Word is Rains wasn’t even the original choice to play the part, but rather offered to Lon Chaney Jr. as a sort of gimmicky tie-in to the 1925 original that starred his father, Lon Chaney Sr. When that went by the wayside, Rains only agreed to play the part of The Phantom as long as his facial disfigurement wasn’t too extreme. Rains still wanted audiences to recognize his face when revealed at the end, which, being a bona fide horror/sci-fi star is a pretty slick move. Regardless, by keeps Rains’ visage more or less intact, he’s allowed to emote in a way an actor simply couldn’t behind the mask or under heavy makeup or prosthetics. As a result, Rains gives a feverish turn as a man mysteriously obsessed with a young operatic chanteuse. And it isn’t just the stints of violence or outbursts of madness either; it’s the quietude, the silence, the stillness Rains shows particularly in the sewer scenery, is just as arresting.

The two aforementioned assets of the film come to a head in the films suspenseful finale. I love this part. When Cludin finally sneaks his way onto the stage on opening night, masquerading among the masked and costumed cast members, we’re thrown into a vertiginous swirl of suspenseful tension. Then Lubin tightens the rope when Claudin climbs up into the domed ceiling of the auditorium. He saws the chain of the humongous chandelier, causing it to plummet down below on one of the female performers. When pandemonium ensues, Claudin absconds Christine to his subterranean lair, at which point he faces a standoff between Anatole and Raoul. When the place collapses, Lubin holds bitter-sweetly on one of the most indelible images in the entire film, and thus of the last 75 years, of a dust-covered mask and violin among the rubble. It’s a haunting image, both sad and satisfying.

WHAT BLOWS NOW: 75 years is a damn long time, so it only stands to reason that a product that old would inevitably show some wear and tear. THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, acclaimed as it is, is no exception. The main issue I had when revisiting the film recently was just how tame and nonthreatening the horror is. Really, this is not a very scary film, but what it lacks in genuine terror it makes up for by the facets enumerated above. The other problem with the film, given today’s standard, is how weak and straightforward some of the musical numbers are. Remember, this was made after the wave of teriffic 1930s musicals, and prior to the heyday of American and French musicals of the 50s and 60s. So by comparison, like the horror elements, the musical set-pieces fall a bit short.

But really, here’s where I think the movie makes the most grievous mistake. In the original screenplay, Claudin is revealed to be Christine’s father, which explains why he’s so obsessed with her success. As it is now, there is absolutely no reason for Claudin’s infatuation with the girl, not even a romantic one. Now, I’m fully aware of the powerful speech Skeet Urlich gives in SCREAM, in which he emphasizes how psychopaths need no motivation (“Did Norman Bates have a motive? Don’t think so!”), and to an extent, I very much agree. And here, Rains plays the part with an icy detachment that plays just as well having no familial connection to Christine. But think about how dynamic the opposite would’ve been. The scene in the end, in which Claudin furiously plays the piano for the girl to sing over, to perceive it through the lens of a mad father tormenting his daughter, automatically makes the scene far more emotionally resonant. I truly believe if they kept this detail in the script, if Claudin was indeed revealed to be Christine’s daughter, a level of dramatic tragedy would be added to the horror aspect en route to creating something that much more memorable. But hey, c'est la vie!

THE VERDICT: This one’s actually a bit tougher than originally thought. While I do think, on the whole, more about THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1943) holds up than doesn’t, it’s not as cut and dry as one might think. What endures without question is the Oscar winning cinematography and art direction, the feverish performance by Claude Rains and the kickass third act. What’s weathered a tad over the past 75 years is the overall scare factor, the staid musical numbers, and, in my opinion, the excised script detail involving Claudin’s relationship to Christine. The net-net however? You know it, THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA still belts it’s mother*cking heart out!

STREAM THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA HERE

GET THE UNIVERSAL CLASSIC MONSTER COMPLETE 30-FILM COLLECTION HERE

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE