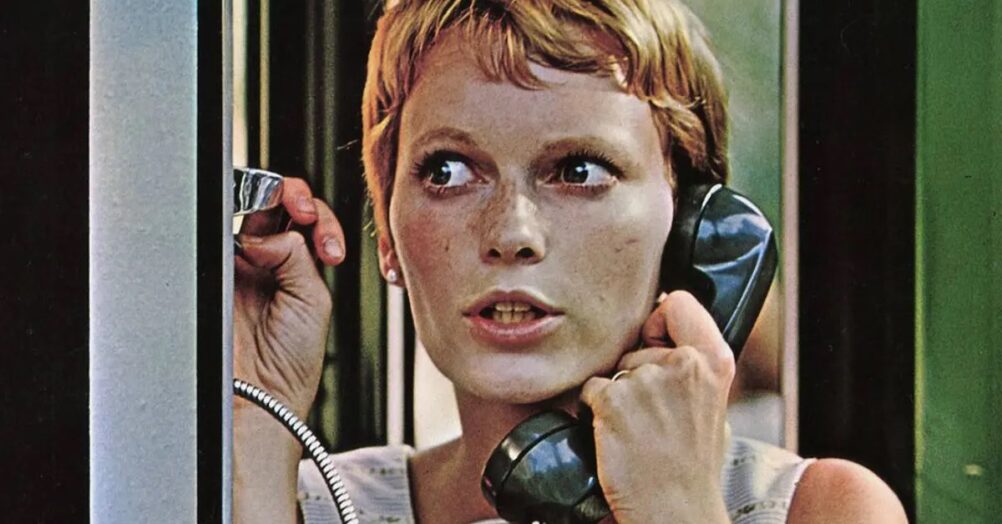

Last month, an episode of our WTF Happened to This Horror Movie? video series looked into the making of director Gus Van Sant’s 1998 version of Psycho to try to figure out why it fell so short of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 version of the story. Now, with a new episode of WTF Happened to This Horror Movie?, we’re taking a behind the scenes look at the making of Hitchcock’s Psycho (watch it HERE) to find out how the “Master of Suspense” crafted one of the greatest movies of all time. Check it out in the embed above!

Scripted by Joseph Stefano and based on a novel by Robert Bloch (which was inspired by news reports on the crimes of Ed Gein), Psycho has the following synopsis:

Marion Crane, on the lam after stealing $40,000 from her employer in order to run away with her boyfriend, Sam Loomis, is overcome by exhaustion during a heavy rainstorm. Traveling on the back roads to avoid the police, she stops for the night at the ramshackle Bates Motel and meets the polite but highly strung proprietor Norman Bates, a young man with an interest in taxidermy and a difficult relationship with his mother.

The film stars Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, John Gavin, and Martin Balsam.

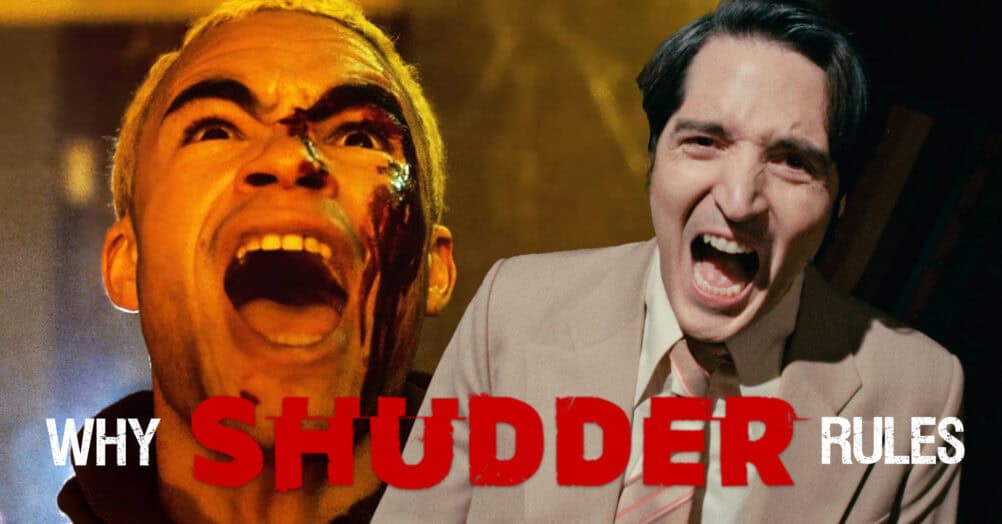

This is what the WTF Happened to This Horror Movie series is all about:

Hollywood has had its fair share of historically troubled productions. Whether it was casting changes, actor deaths, fired directors, in-production rewrites, constant delays, budget cuts or studio edits, these films had every intention to be a blockbuster, but were beset with unforeseen disasters. Sometimes huge hits, sometimes box office bombs. Either way, we have to ask: WTF Happened To This Horror Movie?

The Psycho 1960 episode of WTF Happened to This Horror Movie was Written by Cody Hamman, Edited by Joseph Wilson, Narrated by Jason Hewlett, Produced by Lance Vlcek and John Fallon, and Executive Produced by Berge Garabedian.

Some of the previous episodes of the show can be seen below. To see more, head over to our JoBlo Horror Originals YouTube channel – and subscribe while you’re there!

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE