Last Updated on October 19, 2023

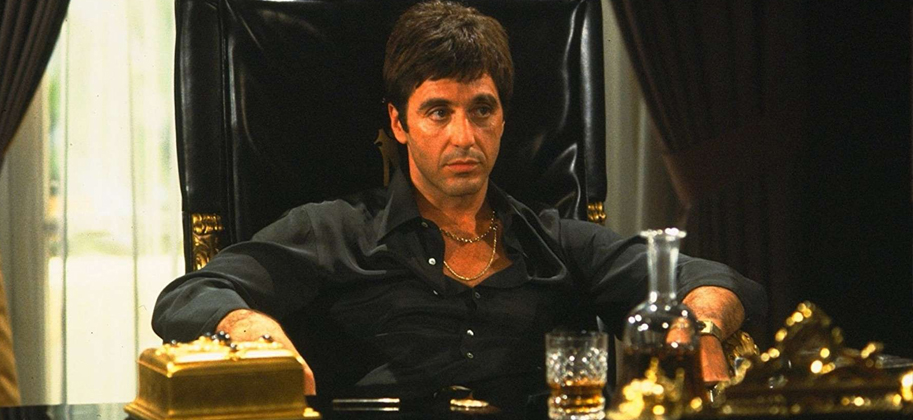

Given the grand lottery that determines Hollywood successes and failures, it’s worth wondering how a bona fide American masterpiece like Brian De Palma’s Scarface has remained such an all-time great movie that continues to be celebrated 40 years later.

After all, the movie faced harsh blowback from the Cuban community at the time, the production was halted by severe weather events, star Al Pacino suffered cuts and burns during production, Michelle Pfeiffer was roundly rebuked by the studio, Oliver Stone was grappling with his own cocaine addiction prior to filming, the budget ballooned out of control and production went three months over schedule, the film was slapped with an X-rating by the MPAA three times for excessive violence before it was released uncut, the critics rejected the movie’s controversial violence and profane language, and perhaps most notably, Brian De Palma replaced legendary director Sidney Lumet and hired Oliver Stone to pen the screenplay, which is now often hailed as one of the best scripts in Hollywood history.

Yet in the end, despite the protests, escalating costs, overwhelming odds, constant shake-ups, and nagging production woes, Scarface proved that even in the censor-heavy 1980s that neutered original filmmaking, a major movie studio like Universal could team with a genuine movie star like Al Pacino, old-school power producer like Martin Bregman, and an auteur-driven director in De Palma that, just like the classic 1932 version of Scarface, ascended to strike a vital nerve in the collective consciousness of pop culture that continues to resonate to this day. A minor miracle indeed, it’s time to chop this motherf*cker up and find out once and for all…WTF Happened To Scarface?!?

According to Pacino himself in a documentary on the Blu-Ray, it was the actor’s idea to remake Scarface after he stumbled into a theater in Los Angeles in the early 80s and watched the original 1932 Howard Hawks version starring Paul Muni. Pacino immediately called his manager and Hollywood producer Martin Bregman, who agreed to remake the film and hired Sidney Lumet to direct after the three worked together on Dog Day Afternoon. While Pacino wanted to retain the 1930s period of the original, it was Lumet’s idea to contemporize the story and set it in modern-day Miami, and to turn Tony Montana into a Cuban character who emigrates to America during the Mariel Boatlift, a topical news story at the time.

Despite Lumet’s invaluable contributions, he and Berman had a falling out over creative differences while the film was in development. Lumet wanted to make a more political picture impugning the Reagan administration for ushering in the cocaine epidemic in the 1980s. Bergman disagreed, ultimately replacing Lumet with Brian De Palma, who loved the script so much he declined to direct Flashdance to make Scarface instead. It was De Palma who hired Oliver Stone to rewrite the script, which Stone initially refused due to his dislike of the original Scarface. But after sitting down with Sidney Lumet directly, Stone had a change of heart. According to Creative Screenwriting, Stone admitted:

“Sidney had a great idea to take the 1930s American prohibition gangster movie and make it into a modern immigrant gangster movie dealing with the same problems that we had then, that we’re prohibiting drugs instead of alcohol. There’s a prohibition against drugs that’s created the same criminal class as (prohibition of alcohol) created the Mafia.”

Once Stone had a workable angle for a story, he began researching the material by interviewing police and criminals throughout Florida and the Caribbean to achieve the utmost authenticity. According to Stone, It got hairy. It gave me all this color. I wanted to do a sun-drenched, tropical third-world gangster, cigar, sexy Miami film.” Wracked by his own cocaine addiction at the time, Stone flew to Paris to write the script, telling Creative Screenwriting:

“I moved to Paris and got out of the cocaine world too because that was another problem for me. I was doing coke at the time, and I really regretted it. I got into a habit of it and I was an addictive personality. I did it, not to an extreme or to a place where I was as destructive as some people, but certainly to where I was going stale mentally. I moved out of L.A. with my wife at the time and moved back to France to try and get into another world and see the world differently. And I wrote the script totally fucking cold sober.”

Part of Stone and Bergman’s independent research entailed gaining access to a wealth of criminal records and video evidence from the U.S. Attorney’s Office and Organized Crime Bureau. The controversial early scene in which Tony watches a man become gorily sliced with a Chainsaw in a shower was taken from a real-life case in Miami at the time, which De Palma felt was vital to sharing with the public to educate them about a new kind of hyper-violent gangster in the world that differed from what audiences were used to in classic Italian mafia movies like The Godfather.

Ironically enough, despite retaining Lumet’s key story ideas and salient themes, Stone told Creative Screenwriting that:

“Sidney Lumet hated my script. I don’t know if he’d say that in public himself, I sound like a petulant screenwriter saying that, I’d rather not say that word. Let me say that Sidney did not understand my script, whereas Bregman wanted to continue in that direction with Al.”

As for the name “Tony Montana,” on the DVD special features, Stone confessed that he named the character after his favorite football player, Joe Montana, “because I was a big 49ers fan and I was looking around for a good name. I thought ‘Montana. The Mountain.’”

Once the final script was in shooting shape, the casting process for Scarface began in earnest, which presented its own series of combative hiccups. While Pacino insisted on playing Tony Montana from the start, believe it or not, Robert De Niro was offered the role but turned it down.

Per a 2019 GQ interview, Pacino admitted that it was De Niro who encouraged him to play Tony Montana and suggested hiring Brian De Palma to direct. De Niro also said that if the project didn’t work out, he’d consider starring as Tony with Martin Scorsese at the helm. Imagine that, a De Niro/Scorsese Scarface could have existed in some alternate version of history. As cool as that would’ve been, 40 years later, it’s impossible to imagine anyone other than Pacino and De Palma at the helm.

Once Pacino was hired, he began a rigorous workout routine that included extensive knife training and boxing with boxer professional Roberto Duran to attain an athletic physique. According to Empire’s Reflections on Scarface, Duran actually helped mold the aggression of Montana, which Pacino claimed noted had a “certain lion in him.” Pacino also drew inspiration from Meryl Streep’s character in Sophie’s Choice, another immigrant looking to realize the American dream. Pacino also spent six months perfecting his Cuban accent for the film.

Steven Bauer, who plays Tony’s best friend Manny Ribera in the movie, was cast in the role without auditioning. John Travolta was actually considered for the role, who De Palma just worked with on the box-office failure Blow Out, but casting director Alixe Gordon spotted Bauer waiting around the auditioning room on the first day of casting and instantly sensed he was right for the part. Bergman and De Palma both agreed after seeing him in person and gave him the role without auditioning, and Bauer became the only authentic Cuban actor in the entire film. According to Pacino, Bauer helped him with his Cuban accent and Spanish dialog thanks to roughly one month of rehearsals that allowed them to fine-tune the characters. To stay in the skin of Tony and remain as authentic as possible, Pacino asked the director of photography John Alonzo to communicate with him by only speaking Spanish while on the set

Far more contentious was the casting of Michelle Pfeiffer as Elvira, Tony’s sexy ice-queen trophy wife whom he can’t quite connect with on a deep emotional level. According to Bregman, Pacino was not sold on Pfeiffer for the role due to her lack of movie experience following her only appearance in Grease 2 and balked at the idea of even giving her an audition. De Palma wasn’t hot on the idea at first, either. Instead, Pacino lobbied for Glenn Close to play Elvira. When Close was not deemed sexy enough by the producers, Bergman fought hard to cast Pfeiffer in the role despite being a relative newcomer. However, Universal wanted big names like Jane Fonda, Goldie Hawn, and Barbara Streisand.

Before Pfeiffer was officially cast, the actresses who auditioned for the role included Geena Davis, Courtney Cox, Sharon Stone, Kelly McGillis, Carrie Fisher, and others. Those who turned down the role included Melanie Griffith, Rosanna Arquette, Kim Bassinger, Kathleen Turner, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Debra Winger, and others. Sigourney Weaver, Karen Allen, Jessica Lange, and Jamie Lee Curtis were also considered to play Elvira before Pfieffer earned the role during her first meeting with De Palma.

Once the casting process was complete, Scarface officially began principal photography with a planned budget of roughly $10-15 million. In the end, the budget ballooned to anywhere from $23-37 million depending on reports at the time from Newsday and Variety (per Vulture), The film shoot would last 24 weeks from November 22, 1982, to May 6, 1983, leaving less than seven months to edit the film before a wide release on December 9, 1983. For Universal, the pressure was mounting to release a financial hit to atone for the growing costs of making the movie.

While Scarface was originally planned to be filmed in Miami, Florida, the Miami Tourism Board was so afraid that the negative depiction of violent drug dealers would hinder their tourism economy that production was forced to relocate to California, where most of the movie was filmed. Moreover, the local Cuban community in Miami felt they were being negatively depicted and protested.

As a result, only two weeks were spent filming in Miami, including the famed Fountainbleau Hotel in Miami Beach, and the rest of the movie was filmed in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara as well as a few pickup shots in New York. For instance, Tony’s lavish mansion was filmed at El Feuridis, a real location in Santa Barbara built based on Roman-style architecture. In addition to real locations, several ornate sets were built on the Universal backlot based on the designs by Visual Consultant Ferdinando Scarfiotti, including the neon-drenched interiors of The Babylon nightclub that Tony often spends time in luxuriating with coke-fueled excess. Per De Palma in Creating Scarface, “I wanted to do a kind of high-tech, neon acrylic vibrant pastels instead of your usual dark film noir. Scarfiotti came up with the whole great look for the movie and he was just a genius.”

Despite the move from Miami to Los Angeles, production was postponed twice due to extreme weather incidents in California, which included unseasonably cold temperatures and partially delayed the production schedule by three months.

According to Stone via Vulture:

“The movie was a nightmare to make, went three months over, and I was on that set all the way to the end. They kept me there. It was like, Who do you have to fuck to get off this ship? It was so slow the way they made it, because Brian’s not an energy guy, and Al’s a retake guy. It cost too much, went over, and was a black sheep from the get-go with Universal.”

The costly production delays also resulted from a slew of onset mishaps and dangerous accidents that caused filming to be postponed. For example, during the hyper-violent finale in which Tony succumbs to 10 brutal gunshot wounds (filmed in March 1983), Pacino accidentally tripped during a fight sequence and fell on an M14 machine gun, badly burning his left hand on the blazing muzzle. Pacino was instantly taken to the Sherman Oaks Burn Center and production was shot down for roughly two weeks while he recovered. If that wasn’t bad enough, a premature bomb explosion injured two stuntmen while Pacino was in the hospital (per Vulture), all but ensuring that Scarface was doomed from the start.

During the scene in which Omar is hung to his death from the helicopter, De Palma claims, “We hung F. Murray (Abraham) from a crane, basically, but the stuntman Dick Dyker had to leap out of the helicopter with a noose around his neck…that had never been done before.”

In the penultimate shot of the film, in which Tony is shot to his death and falls off the balcony into the blood-sodden pool below, famed stuntman Tom Elliot performed the fall without any special FX or any safety wires (Peter Pan Rig), which was extremely dangerous considering there wasn’t any padding in the cement pool and Elliot was descending from 12-feet high into a pool of less than 2-feet of water. After the first take, De Palma felt Elliot’s posture was too balletic and told him to do it again. A problem with the camera’s speed ruined the second take. Even though he was forced to hold his breath for a long time after landing due to De Palma’s insistence on a long take, Elliot nailed the stunt on the third take and that’s the one that’s used in the movie.

Even during the audition process of the iconic scene in which Tony and Elvira argue over their sham marriage, Pfeiffer lost herself in the moment and threw dishes and glassware that broke on the floor and cut Pacino’s finger. “I saw the blood on the floor,” Pfeiffer told Jimmy Fallon in a 2017 interview, adding, “I thought it was my blood, but no, I’d cut this big movie star!” Pfeiffer got the part anyway and remains one of the movie’s many strengths.

Yet, somehow, all of the real brushes with danger during production only make the smashing success of the movie more impressive in retrospect in a kind of timeless, art-imitates-life parable that continues to add to the movie’s growing legend as an all-time great American gangster classic.

Speaking of the iconic final shootout, it’s worth noting that De Palma invited his longtime friend Steven Spielberg onto the set one day while the climatic sequence was being filmed. Spielberg suggested placing a low-angle camera outside as Sosa’s goons swarm in on Tony’s mansion and first enter the house while using grappling hooks. The single shot directed by Spielberg has been retained in the final cut of the film, putting a cool button on De Palma and Spielberg’s days together at USC Film School not too far away or long before.

Five cameras in total were used to film the harrowing finale, according to Alonzo. “We had one on a crane and we had two down below…and we had a slow motion camera that was prepared to shoot the stuntman as he got hit or Pacino as the squibs were going off. We may have had five cameras on that sequence. It probably took more than half a day just to line up exactly where the cameras were going to go and it took two days to get the stunt of the man falling.”

Because Pacino burned himself and was absent for two weeks, De Palma had extra time to film the hyper-violent climax, which only reinforces the themes of 80s excess and materialistic indulgence that permeates the entire movie. Part of what makes the harrowing climax so visceral and authentic are the visible gun flashes that appear on camera, lending the scene a real sense of fire and brimstone.

According to De Palma, “A lot of times when guns are shooting, you don’t see the flash. And so we rigged up something that would synchronize the flashing to the shutter of the camera so that you can see the flashing all the time.”

Alonzo credits Special Effects supervisors Ken Pepiot and Stan Parks for designing “this synchronization system for the weapons so that the camera shutter is open to see the flame and Pacino can’t fire it unless the shutters open it. It sort of drove Pacino crazy a little because he pressed the trigger and it wouldn’t fire until the camera was perfectly in sync. And he got a little testy there because he wanted the freedom of it but it worked out very good.”

As for the million-dollar question of what substance was used to replicate cocaine consumption on screen – it was not real cocaine, contrary to popular rumors that have persisted for years. Instead, powdered baby milk was used, according to De Palma. However, per a Business Insider report, a baby laxative was used to replicate cocaine in the movie. Whatever the substance was, something Pacino likes to keep a secret to retain the mystique of the character, “it wasn’t easy to snort,” according to De Palma, “because it would get in your nose and he’d (Al) be blowing his nose all the time.” As a result, Pacino’s nasal passage was partially damaged while filming.

As for Tony Montana’s “My Little Friend” during the incendiary shootout, the firearm happens to be a custom M16 with an M203 39mm Grenade Launcher. He also uses a custom Colt AR-15 during the shootout. Several prop replicas of the M203 were produced and recycled for subsequent Hollywood productions in the 80s. Among them, Clint Eastwood used one in Heartbreak Ridge and Arnold Schwarzenegger used one in Predator. Yup, that’s Dutch is rocking Tony’s motherf*ckin’ grenade launcher…also at shady ass Colombians…go figure!

Oliver Stone also insisted on equipping Tony with a Berretta Model 81 with Pachmayr grips as his primary sidearm, which he felt was integral to his character’s image.

When it came to scoring the film and creating a unique soundscape for Tony’s coke-riddled world, De Palma routinely denied Universal’s attempts to lace the film with contemporary pop music needle drops. Instead, De Palma hired Oscar-winning Italian record producer Giorgio Moroder to create the score based on his work on Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo. The unforgettable synth new wave electronic orchestrations that resulted have become an indelible aspect of the movie that perfectly echoes the characters and actions they take. Thankfully, De Palma has shot down every request Universal has made to replace the score with hip-hop music, something the studio wanted to do for the 20th anniversary in 2003.

Roughly six weeks before Scarface was set to be released in theaters, the MPAA suddenly tagged the film with an X-rating, citing the infamous opening chainsaw massacre as their primary concern. With well over 200 “F-Bombs” in the film as well, profanity was another terrifying issue for the rating board. The censors requested removing a shot of a severed arm hanging from the shower curtain rod, which De Palma never intended to use anyway. Knowing the severed arm would be controversial, he wittingly sacrificed it to be removed so his real intention of doing a more-is-less, suggestive approach would remain intact (much like his hero Hitchcock did in the Psycho shower scene).

De Palma made the requisite cuts and resubmitted the film, only to receive an X-rating again. “Then I cut it back a third time,” says De Palma, “and they were sort of fixated on how many gun hits were on the clown. ‘The clown, we’re worried about gun hits on the clown?’ So this is the third time I sent it back but I wasn’t gonna cut it anymore. I felt it was against what the material was…and I thought it was affecting the dramatic thrust of the movie.” (per Creating Scarface which you can see on the current Blu-ray).

Along with Martin Bregman, De Palma entered legal arbitration with the MPAA to appeal the decision and resolve the issue, all this just weeks before the movie’s premiere and the increasing pressure of Universal needing a hit film to justify its costs. Bregman brought in a host of professionals, including three psychiatrists, to testify as expert witnesses to argue that Scarface was actually an anti-drug film and that the world needed to know about the kinds of dangerous criminals that are out in the world nowadays. In the end, Bregman and De Palma made such compelling arguments that they won in a landslide 18-2 vote and got the MPAA to give Scarface an R-rating in the nick of time.

The best part of the court ruling is that, because all three versions De Palma submitted were given an X-rating, he wisely went back and submitted his original version rather than the third cut he made with all the excised footage. This means the version of Scarface that we all know and love has not been compromised at all…it’s 100% the version De Palma intended to release.

Ironically enough, outside of Eddie Murphy, Martin Scorsese, and a few others who attended the premiere, Hollywood mostly hated the film when it was officially released in theaters. According to AMC’s “DVD: Much More Movie,” Cher loved the movie, Lucille Ball was incensed over the graphic carnage and bad language, Dustin Hoffman fell asleep while watching it, and writers Kurt Vonnegut and John Irving walked out after the notorious chainsaw scene. Critically speaking, outside of Roger Ebert, Vincent Canby, and a few others, the movie was met with harsh negative reviews that have all since been proven pretty inaccurate and wrongheaded and often forced many of them to print mealy-mouthed retractions. Moreover, negative word of mouth didn’t hurt the film’s box office success, it arguably helped fuel the film’s torrid popularity, which also took off when the movie was released on home video with the subsequent rise of the VHS.

As for Pacino, he’s publicly stated that Tony Montana is his favorite character that he’s played in a movie. According to Oliver Stone, “When I saw the film, I was very proud of it. You know, one of my children. I go into the New York subways and I hear dialog from the picture. I knew that it hit a nerve.”

Scarface premiered in a star-studded New York movie house on December 1, 1983, before opening wide on December 9, 1983. The film grossed $45 million domestically and $66 million globally, good enough to earn back its bloated budget, turn a healthy profit, and justify the painstaking efforts, protests, threats, legal hurdles, and on-set mishaps in the process of making the movie. Although the film was summarily dismissed by critics and many esteemed Hollywood luminaries who were offended by the excessive violence and profanity, the film went on to become an all-time beloved cult classic that inspired countless rappers like Geto Boys and video games like GTA: Vice City. Hell, even Saddam Husein named his money-laundering operation Montana Management after the movie. Pacino himself later thanked rappers for keeping the movie relevant.

The movie also inspired the 2007 video game Scarface: The World Is Yours, set in an alternate reality in which Tony survives the mansion massacre, rebuilds his cocaine empire and vows revenge on Sosa and his men. In 2001, rapper Cuban Link was tapped to write and star in a Scarface sequel titled Son of Tony, but the project was ultimately canceled. Universal has also been planning a quasi-remake of Scarface since 2011, with several names attached in the past decade, including David Ayer, David Yates, Pablo Larrain, and Antoine Fuqua as potential directors. As of now, Luca Guadagnino is still attached to direct the remake, but with his dance card as a director quickly filling up, iI wouldn’t expect this to happen with him at the helm. Perhaps that’s for the best. As enticing as that may sound to some, it’s hard to imagine such a project equaling the original much less eclipsing it.

Honestly, the lore and legend of the movie are so profound and so timeless that it feels like we could go on forever. But that is more or less WTF happened to Scarface. Despite the controversial material, the intense blowback and rabid protest from the Cuban community and Miami Tourism Board, the costly production delays and swollen budgets, the perilous onset mishaps, and the virulent critical response, the movie endured all of the potential pitfalls that could have easily sunk the production at any time along the way and became. In the end, America is still a meritocracy, and the bottom line is that Scarface is simply one of the best movies ever crafted, bar none. Perhaps De Palma sums it up best at the end of Making of Scarface, in which he says: “So in a traditional Hollywood way, where we have a great producer and a great actor and a great director and a great screenwriter, I think we made a really great movie.” Forty years later and it’s safe to say one thing about Scarface and Tony Montana: The World Is Yours indeed!

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE