We all have certain movies we love. Movies we respect without question because of either tradition, childhood love, or because they’ve always been classics. However, as time keeps ticking, do those classics still hold up? Do they remain must-see? So…the point of this column is to determine how a film holds up for a modern horror audience, to see if it stands the Test of Time.

DIRECTED BY MICHAEL WADLEIGH

STARRING ALBERT FINNEY, GREGORY HINES, EDWARD JAMES OLMOS, TOM NOONAN

Here’s a hard noggin to split for all you legit horror fiends: what werewolf flick specifically released in 1981 are you digging most: Is it American Werewolf in London? The Howling? Or, despite earning mostly glowing reviews at the time, is it the still criminally unheralded Wolfen (WATCH IT HERE/OWN IT HERE), Michael Wadleigh’s weird and wickedly jarring tale of lethal lycanthropy? All with their own merits, no doubt, it isn’t a very easy decision to answer, is it?

The question becomes doubly difficult when assessing the films in retrospect, with Wolfen in specific turning 40 years old this past summer. Hailed at the time for boasting a grounded story that doesn’t rely on cheap violent escapism, the film also drew massive plaudits for its stunning cinematography and groundbreaking use of sound and visual POV shots of the werewolf attacks. Albert Finney was also praised for his convincing turn as a New York cop tormented over the grisly rash of hyper-gory animalistic massacres besieging the city. And yet, the film still gets overshadowed by the fu*ked-up ferocious beasts of the two rival werewolf movies listed above and, as a result, is often considered the worst of the three films. Or at least the most forgotten. What do you think? Let us know below. In the meantime, let’s see how Wolfen fairs for real when it’s given the 40-year measuring stick in The Test of Time!

THE STORY: Adapted from the novel The Wolfen by Whitley Strieber (The Hunger, Communion), the film startles with a mesmerically stylish day-for-night opening salvo in which a pair of rich Manhattanites are slaughtered by a mysterious, low-to-the-ground monster whose gliding POV is the first in history to use the thermographic visual template that would later be popularized by Predator and other such flicks (more on that later). Afterward, retired NYPD Captain Dewey Wilson (Finney, in a role that Dustin Hoffman lobbied for but was rejected the only time in his career for a part he so fervently sought due to Wadleigh wanting to work with Finney, his favorite actor) is asked to rejoin the force when the aforesaid massacre turns out to be just one of many plaguing NYC. After terrorists involved with voodoo are blamed for the deaths, Wilson tracks a red herring until he senses something much more animal and ferally atavistic is at work.

After more incredibly cool-looking kills that highlight the novel visual aesthetic take place, Wilson begins digging up intel on Native American lore regarding Canis Lupus, a subspecies of rabid werewolves with a godlike spirit that he later sees viciously maraud a suspect he’s staking out in relation to the terrorists he’s chasing. All this leads to a fun but a rather bathetic showdown with Wolfen on Wall Street, albeit with far less coke and strippers for Di Caprio to indulge. Close though.

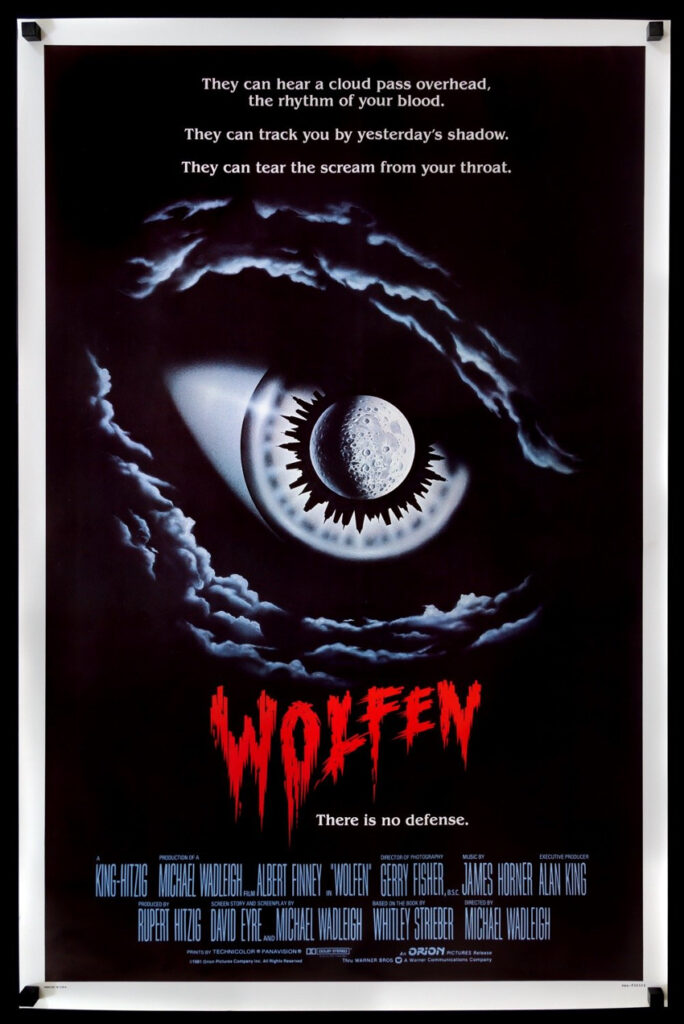

WHAT HOLDS-UP: When watching Wolfen in 2021, the first thing that stands out on a diegetic level is how respectful it ends up treating its lycanthropic lore. When Wilson goes to the bar in the third act and learns from Eddie Holt (Edward James Olmos in a brief but soulful turn) of the Native American Wolfen spirit as extrasensory deities that should be feared, honored, and respected is far more profound and even poetic than most cheap exploitation B-movie fare that werewolf formulas hew to. With lines like “you don’t have the eyes of a hunter, you have the eyes of the dead” or “they can hear the sound of your thoughts” and “they will tear the scream from your throat” (as seen on some posters), lends a kind of mystery and majesty to the beasts that, in a strange way, almost justify their extremity.

I love the way werewolves themselves are depicted in the film: not just as one-dimensional blood-starved beasts, but as sympathetic survivors simply adapting in a kill-or-be-killed world as well, no place more apparent than in NYC. There’s a maturity to the story here that makes this move less reliant on say a showstopping FX-driven werewolf transformation like American Werewolf and The Howling does, which makes for a more grounded and adult-driven story. Sure the themes get a bit pedantic toward the end, but there’s a magnanimity to the way in which the wolves are presented as rightful equals to humans as evolved, hypersensitive animals who both share the same killer instinct and Darwinian survival of the fittest mindset, spirituality, and physicality.

The other aspect of the film that, for the most part, continues to impress 40 years later, is the pioneering visual tableau of the film and sumptuous cinematography by Gerry Fisher (Black Rainbow, Running on Empty). The ensorcelling POV shots of the wolves were filmed using the day-for-night technique and employing a Steadicam and Louma crane to achieve the stylized, graceful, balletic movement that really captures the beauteous dynamism of the wolves that reinforce their natural finesse. Filtered with a candy-colored visual array that vivifies the already visceral onslaught of violence, the death scenes in the film are handled in a way that transcends mere trashy pulp.

There’s a level of exciting immersion to the stalk-and-slay scenes that is almost akin to an ultra-modern, fast-moving, first-person shooter game in the way the camera pans, scrolls, and tracks while constantly hovering forward. At one point the film was delayed because these visual effects couldn’t be done properly, so a new FX company was hired and the production resumed. A wise move, as this remains one of the movie’s strongest attributes. So too is the way in which Fisher photographs New York City, with director Wadleigh’s trademark documentarian-like tours of Central Park Zoo, burnt-out Bronx churches, Coney Island, the Brooklyn Bridge, Federal Hall, etc., all of which help establish a memorably moody glimpse of New York in the early 80s. The film still looks absolutely gorgeous.

Between the gruesome quick-strike throat gouges, gnarly heart rips, decollated heads sent flying through the air, and usage of real, slavering, sharp-fanged wolves on set, ones so dangerous that police had to cordon the filming locations with snipers just in case they went haywire, there’s a genuine level of authentic terror in the film that holds up extremely well since very little of the violence depends on CGI. The deaths are done with practical FX that are partially augmented with the thermographic filter (especially Gregory Hines’ death as the coroner Whittington), synthesizing a really badass visual template that Predator, while a far more popular and better movie, uses to less convincing effect. That is and should always be Wolfen’s lasting legacy.

WHAT BLOWS NOW: Honestly, at 115 minutes, there are a few dry spots in the editing of Wolfen that kind of drag nowadays. But hey, apparently the first cut of the film ran four and a half hours long, so getting a coherent cut under two hours, after having to do reshoots no less (Wadleigh was reportedly replaced by John D. Hancock during reshoots), is pretty impressive. Much of the slog comes from what turns out to be a superfluous terrorist plot that, while mildly interesting when exploring the voodoo subplot, doesn’t pan out or pay off in a satisfying way.

Another minor letdown when viewing the film today is the anticlimactic ending. After setting up a promising third act with truly harrowing eruptions of gore-sodden affronts, not to mention James Horner’s hastily written score (written in 12 days after the original composer was canned, and one that uses parts of Horner’s subsequent score for Aliens), the nocturnal werewolf Wall Street transformation of Wilson and slow-mo action in the high-rise simply doesn’t work. It’s here where the visual effects are the least credible and the violence most underwhelming.

THE VERDICT: In retrospect, Wolfen’s exhilarating technical achievement and importance of introducing the visual trend of thermographic photography is what holds up most about the film. The stylish salvos of gore are fortified because of, not in spite of, the cool-looking werewolf perspectives. More than just a technological gimmick, the engaging POV shots allow the audience to get into the mind of the majestic beasts, which, in addition to the Native American lore, lends tremendous sympathy for the beasts as well as their human prey. It’s the marriage of story and technology that reinforces the themes Wadleigh attempted to convey. Forty years later the intent shines through with impressive results. They say wolves can live to roughly 15 years old, but in the case of Wolfen, the feral bloodline continues to flash its ferocious fangs for nearly thrice as long.

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE